CS-Shapley: Class-wise Shapley Values for Data Valuation in Classification

Stephanie Schoch

Nov 28, 2022

In machine learning settings, there are notable benefits of understanding how individual training instances impact a learning model. For example, through identifying and filtering points that harm the model (e.g. noisy or mislabeled instances), the performance on a subsequent model retraining may increase. We could additionally seek to augment the data by identifying new data instances that are similar to training instances that were highly beneficial to the model. In this setting, we can refer to how an instance impacts a performance metric of choice as the “contribution” of the data point.

The prudent question to ask then becomes one of how to measure this contribution. While we could simply measure the model performance when trained with vs. without the training instance (i.e. Leave-One-Out from (Cook, 1977)), this method has certain drawbacks as it does not satisfy several properties desirable for measuring data contributions and does not always perform as expected in practice. Ghorbani et al. (2019) exemplified this with a concrete example: if we are measuring contribution to a KNN classifier and have two copies of each data point, removal of one point would not change the classifier performance, and each data point would receive a contribution score of 0.

Shapley values have been proposed for use in this context and have proven to be effective for measuring data contributions, and the associated applications. Shapley values, from cooperative game theory, satisfy desirable fairness guarantees due to their underlying axiomatic basis. For a value function \( v(\cdot) \), the Shapley value \( \phi_i(T,A,v) \), for any data point \( i \) is defined as:

\[\phi_i(T,A,v) = \sum_{S\subseteq T\backslash\{i\}} \frac{v(S\cup \{i\}) - v(S)}{n-1 \choose |S|}\]Much of the work in applying Shapley values to data contribution measurement, or data valuation, has sought to develop approximation techniques to mitigate the computational cost of true Shapley computation. Specifically, true Shapley value computation is exponential with respect to the number of data points, and as such, entails an exponential number of model retrainings. One such approximation method is the Truncated Monte Carlo method proposed by Ghorbani et al. (2019), which we adopt in this work. Additional approximation methods can be found listed in the paper.

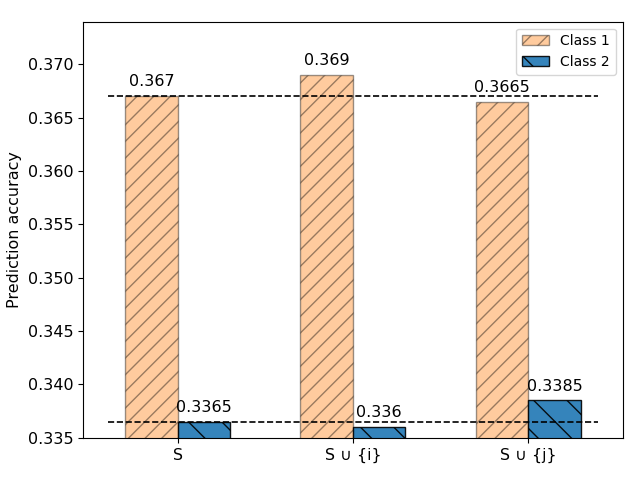

What the existing methods have in common, however, is how the value function underlying Shapley computation is defined. More specifically, the value function is defined over the entire development set (in practice, development accuracy). In this work, we challenge the implicit assumption that full development set metrics are ideal for Shapley computation on classification datasets. Our intuition was that defining the value function in this manner may have limited ability to differentiate helpful or harmful training instances. We provide an example in the figure below.

While we provide more details in the paper, in short, this example shows two training points from the real world CIFAR10 datasets that belong to the same class, cause the same overall development accuracy change, yet data point \( i \) increases in class accuracy while data point \( j \) decreases in-class accuracy. Intuitively, data points that harm their own classes may be mislabeled or otherwise noisy.

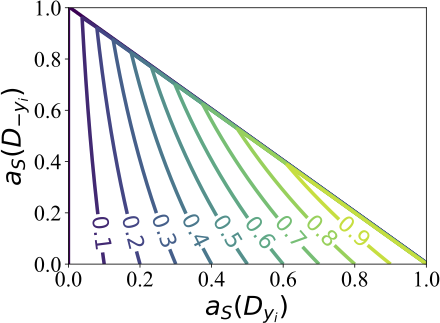

To address this, we define a value function that uses in-class accuracy as a measure of contribution and out-of-class accuracy as a weighting, or discounting, factor. While we demonstrate several desirable properties of this function in the paper, we can illustrate this function in the following contour plot

The effect of the out-of-class accuracy is controlled by the value of the in-class accuracy. In other words, when the in-class accuracy is low, the out-of-class accuracy can essentially be ignored. Conversely , when the in-class accuracy is high, the out-of-class accuracy can have a substantial effect on the valuation of an in-class data point.

In the paper, we demonstrate the efficacy of this value function applied to Shapley-based data valuation using three tasks: high-value data removal, noisy data detection, and transferability of data values. Please see our paper for more details!