Tradeoffs between Invariance- and Sensitivity-based Adversarial Perturbations

Yangfeng Ji and Hannah Chen

Nov 18, 2021

In general, adversarial examples are defined as the ones with small perturbations on original inputs that will fool a model to make wrong predictions. Based on what the prediction error is, we can categorize adversarial examples into two types.

- Sensitivity-based adversarial example: with a small perturbation on \( x \), the ground-truth label remains, but the model prediction is changed;

- Invariance-based adversarial example: with a small perturbation on \( x \), the ground-truth label is changed, but the model prediction remains.

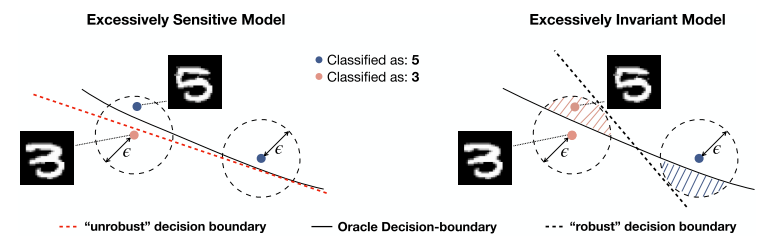

Traditional sensitivity-based adversarial examples are formalized as adding perturbaiton \( \delta \) to an input \( x \) causing incorrect model prediction. The perturbation is usually constrained with \( l_p \) norm. In provably robust training, the defender’s goal is to show that the attacker cannot find any adversarial examples within this \( l_p \) ball. However, optimizing model robustness to \( l_p \)-bounded perturbation, as pointed out by Tramer et al. 2020, may help improve robustness against sensitivity-based examples but could introduce excessive invariance and increase vulnerability to invariance-based examples. This is because the model is excessively protected from sensitivity-based attacks and becomes less sensitive to some real semantic changes, which actually flip the ground-truth labels. In this work, this type of models are called overly-robust models.1 They demonstrated this intuition in the image below.

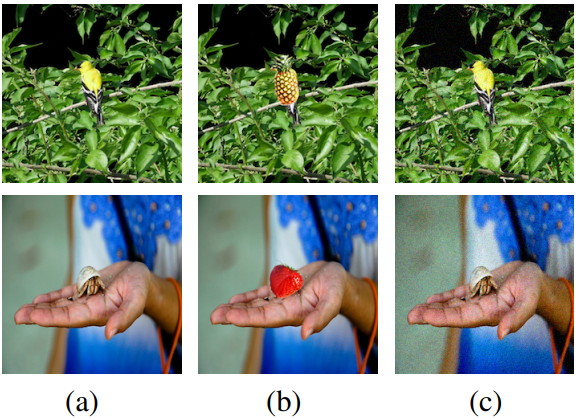

The key concept in Tramer et al. 2020 for understanding this fundamental tradeoff is the distance-oracle misalignment. In general, the misalignment is defined over three example: \( {x,x_1,x_2} \), if their ground-truth labels have the relations: \( \mathcal{O}(x)=\mathcal{O}(x_1) \) and \( \mathcal{O}(x)\not=\mathcal{O}(x_2) \), then the misalignment means \( \text{dist}(x,x_1) \geq \text{dist}(x, x_2) \).2 In other words, although \( x \) and \( x_1 \) share the same label, but there exists an \( x_2 \) that is closer to \( x \) but with a different label. The examples of this misalignment is not difficult to find, at least, in image cases. In the following two examples, the first column is \( x \), the second column is \( x_2 \), and the third column is \( x_1 \). Although the examples in the second column do not have the same labels as the first/third clumns, but they are in the same \( \ell_2 \) ball.

Unfortunately, this misalignment is not an easy issue to solve. As indicated by Lemma 4 in their paper, finding an oracle-aligned distance function \( \text{dist}(\cdot) \) is equally challenging as finding the oracle \( \mathcal{O} \).

In section 5 of Tramer et al. 2020, it further explains the underlying reasons of getting an overly-robust model in adversarial training:

the ability to fit an overly robust model thus relies on the training data not being fully representative of the space to which the oracle assigns labels.

Furthermore, the fact that these models can generalize means

there must exist overly-robust and predictive features in the data — that are not aligned with human perception.

A better way to understand these two statements is to put them together: for a non-representative dataset, there exist some features that are not semantically related to the task but can still make predictions. As long as these features are in the examples, it is possible to flip the semantic meaning of examples but keep the model predictions unchanged.

-

We am not sure whether this is a good naming, but we will keep it in this post. ↩

-

Whether the edge case \( \text{dist}(x,x_1) = \text{dist}(x, x_2) \) can be considered as a misalignment is not explicitly discussed in Tramer et al. 2020 ↩